Donald Trump’s proposed “Board of Peace” for Gaza has quickly become one of the most controversial diplomatic experiments of the post-war period, with several key U.S. partners declining to take part. Their refusals highlight deeper disagreements over how peace-building should work, who should lead it, and how closely any new body must align with the United Nations and international law.

- What Trump’s Gaza “Board of Peace” Proposes

- Why Several Countries Said No

- France: Defending UN-Centered Multilateralism

- Germany: Constitutional Scrutiny and Legal Limits

- Greece and Italy: Europe’s Institutional Caution

- New Zealand: Alignment With the UN Charter

- United Kingdom and Ukraine: Concerns About Membership and Scope

- Global Conflict, Displacement, and the Stakes in Gaza

- The Balance Between Leadership and Legitimacy

- What the Rejections Reveal About Future Peace Efforts

- Conclusion

What Trump’s Gaza “Board of Peace” Proposes

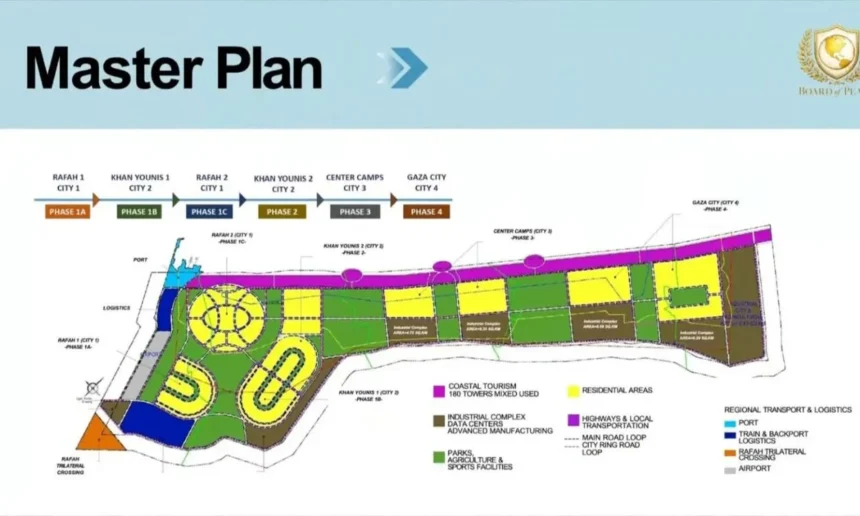

Trump’s “Board of Peace” is framed as a long-term mechanism to oversee reconstruction and political stabilization in Gaza after years of devastating conflict between Israel and Hamas. The initiative was unveiled at the World Economic Forum in Davos, where the administration invited around 60 countries to join a new governance body that would manage funds and major decisions on Gaza’s recovery.

Under its charter, Trump serves as chair with sweeping veto powers over both decisions and membership, and he would remain in that role until he chooses to step down. Countries seeking a permanent seat must commit a very high financial contribution, reportedly around 1 billion dollars, giving the board a strongly transactional character. Supporters argue that a central, well-funded mechanism could speed up rebuilding and create predictable structures for donors and local authorities.

At the same time, the board sits alongside existing international frameworks rather than under them, which many governments view as a departure from the UN-led approach that has traditionally guided post-conflict recovery. This tension between a bespoke political project and multilateral norms is at the heart of the opposition from several countries that have rejected invitations.

Why Several Countries Said No

A number of U.S. allies and partners have now declined to join the Board of Peace, including France, Germany, Greece, Italy, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and Ukraine. Many of them share overlapping concerns about legitimacy, legal constraints, and the concentration of authority in the hands of a single political figure.

Their objections generally fall into four recurring themes:

- The board’s distance from the UN Charter and Security Council framework

- Constitutional and legal limits at home

- Discomfort with Trump’s personal veto power and open-ended mandate

- Unease about sharing the table with states viewed as destabilizing

These reasons are not unique to the Gaza context; they echo long-running debates about how power is distributed in global governance and how far individual leaders can shape international institutions around their own political projects.

France: Defending UN-Centered Multilateralism

France’s government was among the first to publicly decline, emphasizing its commitment to a UN-centered system for peace and security. French officials warned that the board’s design, including the chair’s extensive powers and self-selected successor, sits “far” from the spirit and structure of the UN Charter.

Paris also signaled discomfort with the idea that one political leader, rather than a treaty-based institution, would effectively control membership and the long-term direction of the project. French diplomacy has long backed a two‑state solution for Israelis and Palestinians within an internationally agreed framework, making it wary of parallel arrangements that appear to bypass existing UN mechanisms.

The French refusal also underscores a broader European instinct: major decisions on Gaza’s future, in this view, should remain anchored in collective bodies such as the UN Security Council, the European Union, and established donor coordination platforms. That stance reflects a belief that sustainable peace rests less on individual leadership and more on predictable, rules-based cooperation.

Germany: Constitutional Scrutiny and Legal Limits

Germany likewise turned down the invitation, citing constitutional and legal constraints on joining an external body structured in this way. Berlin expressed support for progress in Gaza but argued that the board’s current design could not be reconciled with its domestic legal framework.

German leaders have repeatedly emphasized that any foreign engagement, especially in conflict and post-conflict settings, must respect parliamentary oversight and constitutional principles. A body in which one individual holds sweeping veto powers, indefinitely, sits uneasily with that approach.

At the same time, Germany has remained a major contributor to humanitarian relief and development in crisis-affected regions through the UN and international financial institutions. This dual posture—rejecting the structure of Trump’s board while continuing to support Gaza through established channels—illustrates how states can oppose a specific initiative without retreating from broader peace-building responsibilities.

Greece and Italy: Europe’s Institutional Caution

Greece’s leadership made clear that the proposed board goes beyond what the UN Security Council has mandated for Gaza, raising questions about overlap and legitimacy. Greek officials have argued that European states should be wary of joining structures that appear to exceed or sidestep the role of existing UN bodies in managing peace and security.

Italy’s prime minister, meanwhile, pointed to domestic constitutional constraints and the need for extensive parliamentary and presidential review before Rome could even consider membership. The government described parts of the board’s charter as incompatible with Italy’s legal order, at least in the short term, effectively ruling out rapid accession.

Both countries signaled that they are open to cooperation on Gaza’s reconstruction but prefer arrangements that are clearly embedded in international law and their own constitutional systems. Their caution reflects a long European tradition of subjecting external commitments to robust domestic scrutiny, particularly when those commitments involve security, finance, and long-term international governance.

New Zealand: Alignment With the UN Charter

New Zealand became one of the latest countries to reject the invitation, emphasizing that any durable peace mechanism for Gaza must line up closely with the UN Charter. Wellington highlighted the importance of regional actors and existing institutions, arguing that many states—especially in and around the Middle East—are already deeply engaged in Gaza’s future.

New Zealand’s foreign minister underscored that while the country supports the goals of reconstruction and stability, it questions whether this particular board is the right vehicle. For a middle power with a strong tradition of backing multilateral solutions, the priority is to strengthen, rather than duplicate, international structures that help safeguard civilians and promote negotiated settlements.

United Kingdom and Ukraine: Concerns About Membership and Scope

The United Kingdom has declined to participate, describing the agreement underpinning the Board of Peace as a kind of legal treaty raising far‑reaching issues beyond Gaza alone. British officials also voiced worries about the presence and role of Russia within the board, given ongoing tensions and diverging security interests.

Ukraine has likewise rejected the invitation, objecting strongly to the inclusion of Russia and Belarus in a body branded as a vehicle for peace. Ukrainian lawmakers have called it paradoxical that states they view as major violators of international law would sit on a governance structure supposed to advance stability and reconstruction.

These objections underscore a wider point: who sits at the table often matters as much as the mandate itself. When participants include governments seen as active parties in other conflicts, questions inevitably arise about credibility, accountability, and the consistency of their commitments to international norms.

Global Conflict, Displacement, and the Stakes in Gaza

The debate around the Gaza Board of Peace is unfolding against a backdrop of intensifying global displacement and protracted crises. UN agencies report that well over one hundred million people worldwide have been forced from their homes by conflict, persecution, and violence, representing a growing share of the global population. In Gaza alone, UN assessments show that a large majority of residents have been uprooted, with millions of Palestinians registered as refugees under the UN’s dedicated relief agency.

These figures highlight why the design of any new peace or reconstruction mechanism matters. When institutions lack broad legitimacy or appear to sideline established multilateral frameworks, they risk weakening the coordinated action needed to protect civilians, support refugees, and rebuild shattered societies. Durable arrangements typically require predictable funding, shared decision‑making, and clear lines of accountability—features that many of the board’s critics argue are not yet fully present in Trump’s proposal.

The Balance Between Leadership and Legitimacy

Supporters of the Board of Peace often argue that strong, centralized leadership can cut through gridlock and deliver concrete results faster than traditional multilateral processes. They see a well-funded, focused structure, backed by willing states, as a way to mobilize resources and impose discipline on complex reconstruction efforts.

Yet the countries that have refused to join are effectively making the opposite case: that long‑term peace depends less on speed and more on broad consent and legal solidity. For them, anchoring reconstruction in the UN Charter, ensuring that no single leader can dominate decisions indefinitely, and carefully vetting partners are non‑negotiable principles.

This tension between decisive leadership and institutional legitimacy is not unique to Gaza. It recurs whenever new peace initiatives, coalitions, or governance bodies emerge outside familiar multilateral channels, especially when they carry large financial requirements and extensive political symbolism. How states choose between these models influences not just one territory’s future, but the evolving architecture of global conflict management.

What the Rejections Reveal About Future Peace Efforts

The refusals from France, Germany, Greece, Italy, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Ukraine, and others suggest that any enduring framework for Gaza will need to do three things well.

First, it must sit comfortably within the broader system of international law and the UN Charter, rather than appearing to compete with it. Second, it has to distribute authority more evenly, reassuring states that no single actor can shape outcomes unilaterally or indefinitely. Third, it needs to ensure that participants themselves are widely seen as credible guardians of peace, not as protagonists in other unresolved conflicts.

In that sense, the Board of Peace debate functions as a test case for how the world will organize future reconstruction and peace-building efforts—from the Middle East to other regions strained by violence and displacement. With tens of millions of people still uprooted by war, and many conflicts dragging on for years, the search for governance models that combine effective leadership with broad-based legitimacy remains an urgent global priority.

Conclusion

Trump’s Gaza “Board of Peace” has exposed sharp divides over who should lead peace-building and under what rules. Countries declining his invitation are not rejecting reconstruction in Gaza; they are signaling that any lasting mechanism must be firmly grounded in international law, shared authority, and widely trusted institutions. As conflicts continue to uproot communities worldwide, these choices will shape not only Gaza’s future, but the broader evolution of global peace and security architecture.