Ireland’s deputy prime minister (Tánaiste) Simon Harris has warned that there are “very serious red flags” surrounding US President Donald Trump’s newly announced Board of Peace, signaling that Ireland is highly unlikely to participate in the initiative as currently designed. He said he could not see any scenario in which Ireland would join the body in its present form, citing concerns over both its mandate and its membership. As reported by Gráinne Ní Aodha of the Press Association, Harris described the evolution of the Board of Peace from a narrowly focused Middle East ceasefire oversight mechanism into a much broader grouping involving dozens of countries and controversial leaders.

According to reporting in the Irish and UK press, the Board of Peace was initially envisaged as a small body to help oversee implementation of a Gaza ceasefire plan that received United Nations backing in November. That earlier vision reportedly prompted interest from Ireland and other European states, which saw potential to contribute expertise in conflict resolution and decommissioning processes. However, Harris now argues that the initiative unveiled by Trump at the World Economic Forum in Davos diverges sharply from those original discussions and raises new political and ethical questions.

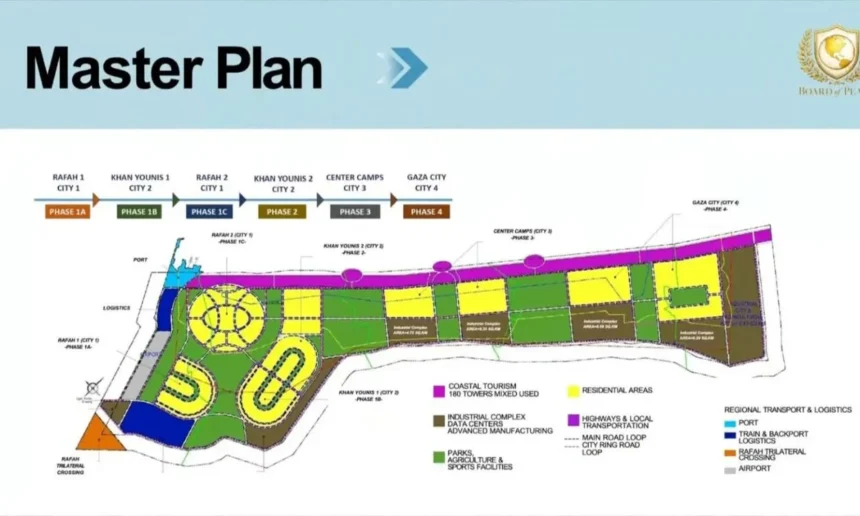

At a signing event in Davos, Trump portrayed the Board of Peace as having the potential to be “one of the most consequential bodies ever created” and said he was honored to serve as its chairman. According to media coverage of the event, dozens of states have been invited to join, broadening the remit beyond Gaza and the original ceasefire-focused mandate. This expansion, combined with the involvement of certain proposed members, has fueled skepticism across several European capitals.

Context and reactions: Why is Ireland concerned?

Harris has highlighted two main areas of concern: the absence of explicit reference to Gaza in the board’s current framing and the proposed participation of Russian President Vladimir Putin. He told Ireland’s parliament, the Dáil, that there is no mention of Gaza in the latest iteration of the proposal and argued that “anything Putin is considering joining with the word ‘peace’ in it does not sit well.” According to Irish media, he stressed that such involvement raises credibility issues for any body presenting itself as a peace mechanism.

In the Dáil, Harris was questioned by Social Democrats deputy leader Cian O’Callaghan, who pressed the government to formally rule out Irish participation. O’Callaghan strongly criticized the lineup of proposed members, referring to it as a “board of autocrats and war criminals” in light of the inclusion of leaders such as Putin, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenko. He also noted that Netanyahu, who faces war crimes charges, did not attend the Davos ceremony due to concerns over arrest risk, underscoring the controversy around the board’s composition.

Harris responded that the Taoiseach Micheál Martin’s decision not to attend the Davos signing ceremony was “entirely responsible” and reflected the government’s stance. He indicated that, from his perspective and that of other cabinet members, Ireland cannot envisage joining the Board of Peace as it stands. According to UK and Irish reports, Harris also pointed out that no European Union leader took part in the ceremony, with the exception of Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, a close ally of Trump, underscoring a broader European unease.

Supporting details and wider European response

As reported by Gráinne Ní Aodha for the Press Association, Harris contrasted the current Board of Peace proposal with the earlier UN-linked Gaza plan that had drawn tentative support from Ireland and other European states. In that earlier context, he said, Dublin was “eager to play a constructive role” and believed it could bring experience in conflict resolution and disarmament to a narrowly focused, clearly defined mission. The shift to a broader and more politically contentious body, he suggested, has fundamentally altered that calculation.

According to regional media coverage, several European countries have already moved to distance themselves from the Board of Peace. States such as Sweden, Norway, France, Slovenia and the United Kingdom have reportedly indicated they will not sign up to the initiative. Critics in the Irish parliament have argued that Ireland should explicitly align with these positions and send a clear signal that it will not take part.

At the same time, Harris has emphasized that the issue will be the subject of further discussion at the European Council. He indicated that EU leaders are likely to exchange views on the board’s scope, membership and implications for existing international peace and security mechanisms. The absence of most European leaders from the Davos ceremony is being interpreted as an early indicator of skepticism, but formal joint positions may take time to emerge.

Implications and future developments: What happens next?

A key immediate implication is that Ireland is positioning itself against participation in the Board of Peace unless its structure and mandate change significantly. Harris’s comments suggest that Dublin’s threshold for involvement includes clear reference to Gaza, a credible and narrowly defined peace mission, and a membership roster that does not undermine the body’s legitimacy. The government is expected to maintain this stance in conversations at both EU and UN levels.

For Trump’s administration, the reaction from Ireland and several European states raises questions about how broadly the Board of Peace will be embraced outside a core group of allies. If major EU countries and other democracies remain on the sidelines, the board could struggle to gain traction as a broadly recognized conflict-resolution platform. Future developments are likely to hinge on whether its mandate is clarified, which states formally join, and how it interacts with existing international frameworks such as the United Nations.

In Ireland, opposition parties may continue to use the issue to pressure the government to give an unequivocal public commitment not to participate. Parliamentary debates are likely to track developments at the European Council and any further US announcements detailing the board’s rules, remit and activities. For now, Harris’s characterization of “very serious red flags” underlines that Ireland views the current proposal as incompatible with its foreign policy priorities and its approach to international peace efforts.

Ireland’s stance, in line with decisions taken by several other European governments, underscores the political sensitivity surrounding Trump’s Board of Peace and the contested nature of its claim to be a credible vehicle for advancing peace. How the initiative evolves, and whether it can address concerns raised in Dublin and other capitals, will help determine whether it becomes a central diplomatic forum or remains a divisive project with limited international buy-in.