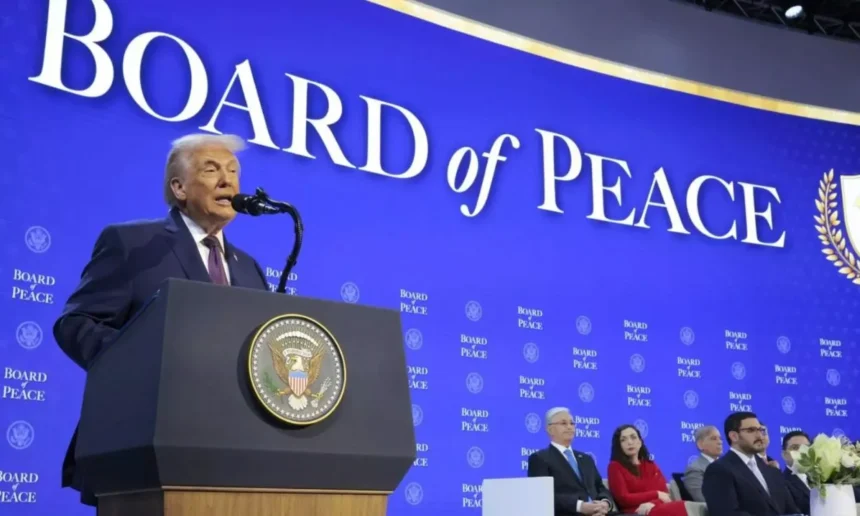

According to Türkiye Today, President Donald Trump has launched a new international “Board of Peace” with 26 founding member states, notably excluding major European powers such as France, Germany and the United Kingdom. The announcement reportedly followed Trump’s introduction of the initiative at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. An official account on X then released the first roster, which includes countries such as Türkiye, Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Invitations were said to have gone to about 50 heads of state, who gradually disclosed that they had received proposals to join.

As reported by Türkiye Today, the Board of Peace was initially framed as a mechanism to oversee a ceasefire and reconstruction in Gaza, but the adopted charter sets a much broader mandate. The mission is described as supporting peace-building “in all areas affected by, or at risk of, conflict,” signaling an open-ended geographic and thematic scope. Detailed rules for leadership, budgeting and operations have not yet been made public. This has raised questions about how the board will function alongside existing international institutions.

Türkiye Today notes that the United States rescinded Canada’s invitation after Prime Minister Mark Carney used his Davos speech to warn against economic coercion by major powers. Russia is reported as excluded from the founding members, even though President Vladimir Putin indicated willingness to allocate a substantial sum from frozen Russian assets to support the board’s budget. Belarus, by contrast, is described as having accepted an invitation, while Ukraine has questioned how it could share a platform with Russia and Belarus amid ongoing war. These choices contribute to a perception of a highly selective and politically charged membership.

How are Europe and other actors reacting?

According to Türkiye Today, the absence of major Western European states comes after a series of disputes between Trump and European leaders over trade, tariffs and issues such as his earlier threats involving Greenland, a Danish territory. These tensions appear to inform European skepticism toward a new U.S.-led body that operates outside traditional multilateral frameworks. The report emphasizes that key European powers are missing from the founding list but does not offer a full breakdown of which governments declined or were never invited. The omission of Europe’s largest economies underscores their unease with Trump’s approach to conflict management and diplomacy.

The article reports that Belarus agreed to join as a founding member, clearly aligning itself with Trump’s proposed architecture. Ukraine, however, has voiced doubts about participating in a body that includes both Russia and Belarus as potential members, given the ongoing conflict on its territory. Türkiye Today indicates that Canada’s invitation was explicitly withdrawn, highlighting that the final list of 26 members reflects not only states’ choices but also Washington’s decisions to include or exclude partners. This contrasts with the more universal, treaty-based membership of institutions like the United Nations.

The outlet adds that Russia’s exclusion, despite Putin’s stated interest in contributing frozen assets, raises questions about the board’s geopolitical orientation. Trump publicly called the idea of Russian funding “interesting,” yet this did not lead to Russian membership. With major EU powers also absent, the initial composition leans toward certain regional partners, particularly in the Middle East and among states like Türkiye and Belarus. The reported lineup suggests that the Board of Peace’s founding structure mirrors current strategic alignments and rivalries.

Supporting details and expert perspectives

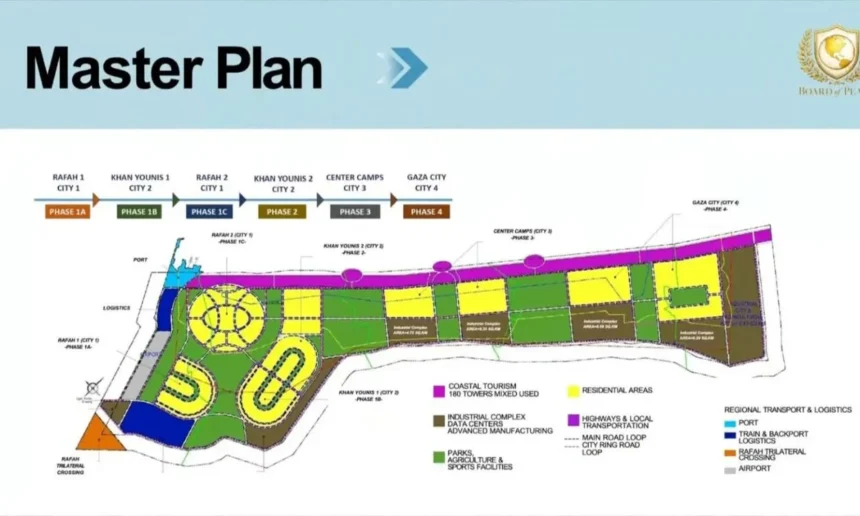

Türkiye Today reports that, although the Board of Peace was introduced in the context of Gaza’s reconstruction, the final charter omits explicit references tying it solely or primarily to that conflict. Instead, the mandate covers a wide range of conflict or high-risk areas, giving the board flexibility to engage in multiple crises. This expansion from a specific Gaza-focused mechanism to a global remit has fueled concern among some governments and observers. They worry the board could evolve into a parallel structure to existing international organizations rather than a strictly temporary or limited initiative.

According to the same outlet, the initiative was initially linked to UN Security Council Resolution 2803, adopted in November and associated with Gaza’s reconstruction. However, Türkiye Today notes that the board’s charter does not mirror the resolution’s narrower, time-limited scope. The body is instead presented as able to act in different conflict zones and to determine its own lifespan. Key details on internal governance, decision-making procedures and funding remain unclear, leaving diplomats and analysts to infer how it might operate in practice.

The report further explains that governments are assessing invitations through the lens of their wider relationships with Washington and their strategic priorities. States closely aligned with U.S. security and political agendas appear prominently among the 26 members. Others, particularly major EU countries and Canada, have stayed out or seen invitations withdrawn after high-profile disagreements with Trump’s administration. This pattern reinforces the view that the Board of Peace is a selective initiative reflecting present power dynamics rather than a universally endorsed multilateral forum.

What are the implications and what comes next?

As reported by Türkiye Today, a central point of contention is the breadth of the board’s mandate and the discretion granted to its leadership. The charter is said to allow the Board of Peace to dissolve “at the discretion of the Chairman as deemed necessary or appropriate,” without fixed terms or external checks. In the absence of detailed procedural safeguards, some observers fear that significant influence over conflict and reconstruction decisions could rest with a limited group of states. The sidelining of major European powers at the founding stage is likely to intensify discussions about legitimacy and accountability.

The outlet also highlights lingering uncertainty about how the Board of Peace will interact with the United Nations and existing peace and security architectures. The move from a Gaza-specific, transitional mechanism envisioned under Resolution 2803 to a broad, standing body raises concerns about institutional overlap or competition. Timelines for when the board will begin operations in particular conflict zones, and how it will coordinate with UN agencies and other actors, remain unspecified. This leaves governments, humanitarian organizations and affected populations waiting for clearer guidance.

Looking ahead, Türkiye Today suggests that the board’s future shape and influence will depend heavily on whether more countries decide to join and whether its charter evolves. If key European and other skeptical states remain outside, the board may function as an alternative track for a coalition of U.S.-aligned partners rather than a widely accepted global mechanism. Conversely, changes to its mandate, greater transparency and closer coordination with existing institutions could affect how it is perceived and used. For now, the creation of the 26-nation Board of Peace, without major European powers and amid several high-profile exclusions, underscores shifting geopolitical fault lines over who defines the rules of post-conflict reconstruction and peace-building.