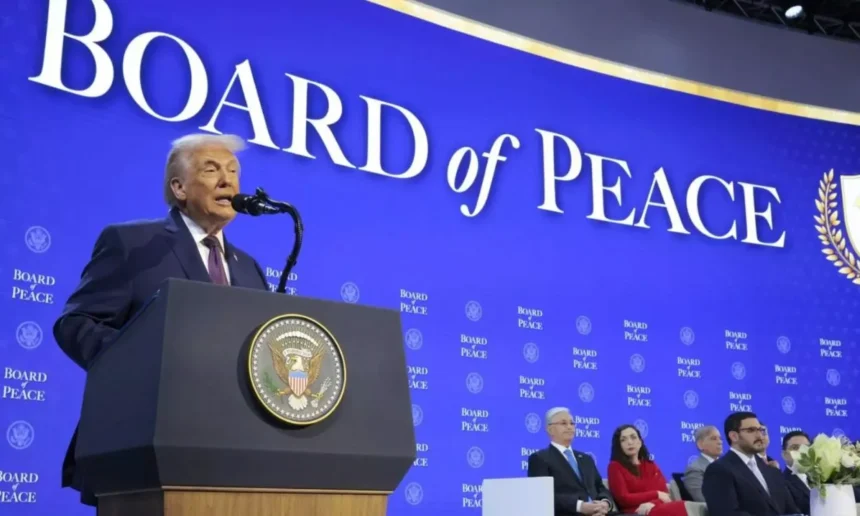

As reported by Madhyamam, the article “Peace without Palestinians isn’t peace—it’s power” examines the announcement of a proposed “Board of Peace” that is being presented as a mechanism to shape Gaza’s post-war future and restore stability. According to Madhyamam, this initiative is framed as a serious step toward ending violence and rebuilding Gaza, but it is criticized for excluding Palestinians from meaningful participation in the process. The piece argues that Palestinians, despite being the population most directly affected by the war and occupation, are being treated primarily as a humanitarian concern to be managed rather than as a political community whose rights and agency must be central to any genuine peace effort. The analysis highlights that this exclusion is described as deliberate, not accidental, and is presented as central to understanding the power dynamics behind the initiative.

The article, as summarized by Madhyamam, situates this “Board of Peace” within a broader pattern in international politics where peace frameworks are negotiated and implemented by powerful states and elites, often without the participation or consent of the affected population. It notes that the board is portrayed as acting in the name of peace and reconstruction while effectively treating Palestinians as objects of policy rather than subjects of rights. According to the same reporting, this raises questions about the legitimacy of such processes and the extent to which they prioritize order and control over justice and self-determination.

Who is being excluded from “peace”?

According to Madhyamam, the central critique of the “Board of Peace” is that Palestinians themselves have been systematically sidelined from decisions about Gaza’s future. The article reports that the board and its backers promote a vision of peace that is “done to” Palestinians rather than “made with” them, emphasizing that their political demands, grievances, and aspirations are largely absent from the framework. This approach is presented as reducing Palestinian suffering to a problem of humanitarian management—food, aid, reconstruction—while avoiding the underlying issues of occupation, displacement, and rights.

The column further notes that for readers in the Global South, this pattern echoes colonial and postcolonial histories where imperial powers designed peace plans, mandates, and partitions that claimed to be benevolent but were negotiated among outside actors. According to Madhyamam’s analysis, such arrangements often brought what it describes as “order without dignity” and “stability without freedom,” suggesting that similar dynamics may be at work in current proposals for Gaza. The report links this critique to a broader warning that excluding the primary affected community from any settlement risks creating arrangements that are more about control than reconciliation.

Supporting details and expert framing

As reported by Madhyamam, the “Board of Peace” is described as including or celebrating figures accused of involvement in serious human rights abuses and war crimes, while Palestinians who have suffered in the conflict remain outside the decision-making circle. The article points out that this composition raises concerns about the credibility of the initiative as a vehicle for justice, given that some of the actors associated with it face accusations that are being examined by international judicial bodies. According to the same outlet, this juxtaposition—elevating powerful figures accused of grave crimes while sidelining victims—undermines the moral and legal foundations that genuine peace processes are expected to uphold.

The article draws on the language and principles of international law, noting that post–Second World War legal frameworks were built on the premise that crimes such as war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide must not be shielded by political power or forgotten over time. Madhyamam reports that, in the columnist’s view, the current configuration of the “Board of Peace” reverses that principle by normalizing or rewarding power even when it is associated with mass civilian harm. This is framed as a broader warning that when accountability is treated as an obstacle rather than a cornerstone of peace, the resulting arrangements risk being seen as instruments of domination rather than reconciliation.

What are the implications and what comes next?

According to Madhyamam, the article argues that arrangements built on the exclusion of Palestinians may produce short-term calm or “management” of the situation but are unlikely to bring a durable settlement. The board’s approach is characterized as seeking stability without addressing core grievances, a strategy the piece suggests may delay rather than resolve underlying conflicts. The columnist, as summarized by the outlet, contends that peace processes that prioritize managing dissent and resistance over engaging with demands for rights and self-determination tend to be fragile.

The article further notes that historical precedents—including colonial mandates and imposed post-conflict settlements—show that peace frameworks which marginalize affected populations often give way to renewed unrest or conflict. According to Madhyamam, the core implication is that any long-term, legitimate peace in Gaza and for Palestinians more broadly will require centering Palestinian political agency, consent, and rights rather than treating them as variables to be controlled. The piece closes with a clear warning that efforts to construct peace without Palestinian participation may postpone a reckoning but cannot permanently avoid it.

In summary, the Madhyamam column presents the “Board of Peace” as an example of a broader pattern in which powerful actors use the language of peace to entrench control while excluding the people whose lives are most directly at stake. It emphasizes that without Palestinian participation and accountability for alleged grave crimes, any resulting framework risks being perceived less as genuine peace and more as an exercise of power.