As reported by CNN, President Donald Trump said his newly created Board of Peace, initially framed as a vehicle to oversee Gaza’s reconstruction, “might” one day take the place of the United Nations, raising concern among diplomats and humanitarian officials about the future of the UN’s role in conflict zones. According to CNN, Trump criticized the UN’s record during a White House appearance, arguing that it had “never lived up to its potential” and suggesting his board could assume broader responsibilities beyond Gaza. The Board of Peace is tied to the administration’s Gaza reconstruction vision and is structured as an international organization with an open invitation to states willing to join.

According to CNN, a draft charter circulated to potential members describes the Board of Peace as an international body aimed at fostering stability and “enduring peace” in conflict-affected areas, but makes no explicit mention of Gaza despite the administration’s presentation of the board as central to the territory’s rebuilding. The report says the White House has pitched the initiative as a long-term framework that Trump would chair indefinitely, with his role ending only through voluntary resignation or a unanimous vote of the Executive Board declaring incapacity. The charter would also allow a future US president to designate another American representative to serve alongside Trump on the board.

According to Reuters, Trump formally launched the Board of Peace at a high-profile ceremony in Davos, Switzerland, describing it as an institution that could address global challenges far beyond Gaza while insisting at that event that it was not explicitly designed as a replacement for the UN. Reuters reports that some governments and analysts nonetheless view the plan as a potential rival structure, given the breadth of its stated mandate and the prominence of US political figures and allies involved.

Context and reactions: How are governments and experts responding?

According to CNN, the Board of Peace’s proposed governance structure has drawn criticism because board members would serve three‑year terms, while countries seeking a permanent seat are being asked to commit a contribution of 1 billion dollars, a level that several diplomats said would require careful political and financial scrutiny. A US official told CNN that the 1‑billion‑dollar figure is not a formal entry fee and would not automatically bind every country to the same funding obligation, but diplomats from invited states said such a sum would still be difficult to justify domestically. One ambassador from an invited country said their government would need to “study” the commitment because the amount was high relative to their budget, according to CNN.

According to Al Jazeera, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva accused Trump of attempting to “create a new UN” through the Board of Peace, warning that such parallel structures could undermine established multilateral institutions. Al Jazeera reports that Lula raised concerns about legitimacy and accountability, arguing that the UN, despite its flaws, remains the primary forum for international decision‑making.

CNN reports that Irish Foreign Minister Helen McEntee said Ireland would examine the invitation but stressed that the United Nations has a “unique mandate” to maintain international peace and security and that the primacy of international law “is more important now than ever.” She suggested the entity outlined by Washington appeared to extend beyond Gaza, reinforcing fears that it could evolve into a broader alternative to the UN system.

According to CNN, Tom Fletcher, described as the UN’s top humanitarian official in the report, stated that Trump’s Board of Peace will not replace the United Nations and emphasized that the UN’s existing humanitarian and peacekeeping work remains central to the international system. Former US Middle East negotiator Aaron David Miller told CNN that the idea of supplanting the UN with Trump’s board belongs “to a galaxy far away” and argued that conflicts are typically resolved through direct mediation between parties rather than through new overarching organizations. He noted that the UN’s decades‑long record, including its Security Council and extensive humanitarian operations, would be extremely difficult to replicate or displace.

Supporting details: How is the Board of Peace structured and funded?

According to CNN, a “founding Executive Board” has been proposed that would include figures such as Trump’s son‑in‑law Jared Kushner, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, a special envoy, and former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair. The Executive Board would oversee strategic decisions, with Trump as its chair, while member states would hold rotating or permanent seats depending on their financial and political commitments.

Reuters reports that Trump has invited a range of countries to join and is seeking signatures on the board’s charter, with some US partners including the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain signaling they would participate, while others, such as France, have declined. According to CNN, some countries that were not initially invited have expressed interest in joining and even in paying the 1‑billion‑dollar sum to secure a permanent seat, highlighting the potential geopolitical weight attached to membership.

According to CNN, US officials have said funds tied to permanent seats would be directed toward Gaza’s reconstruction, including early‑stage talks with contractors to rebuild infrastructure, although no final plans have been agreed. Miller compared the large financial commitment to a membership at Trump’s Mar‑a‑Lago club, arguing that it could be politically contentious for democratically elected governments asked to justify such spending for a new body whose authority and effectiveness are not yet proven.

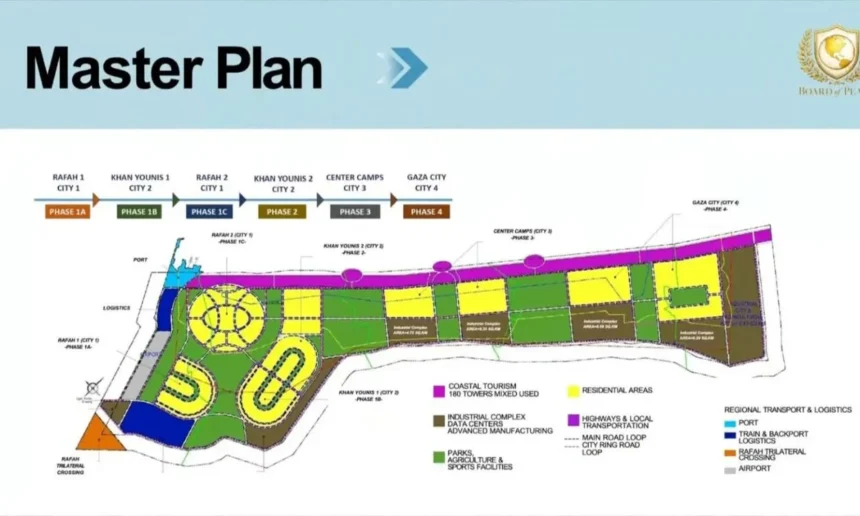

Analysts cited by the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW) in Warsaw have noted that in the context of Gaza, Trump’s broader 20‑point peace plan and the Board of Peace concept offer Israel an opening to scale back its military involvement while shifting reconstruction to a US‑led framework. OSW points out that the initiative also aligns with Trump’s longstanding criticism of multilateral institutions and his preference for ad‑hoc coalitions of states and private investors.

Implications and future developments: What could happen next?

According to Reuters, some Western diplomats fear that if the Board of Peace gains momentum, it could dilute support for existing UN agencies, especially in conflict‑affected areas where funding is already under strain. However, many member states are expected to approach the initiative cautiously, balancing potential influence within the new structure against concerns about its cost, governance and impact on the UN.

CNN reports that the board’s future credibility may depend on tangible results in Gaza, where reconstruction needs are vast and politically sensitive. Experts cited in that report argue that if the Board of Peace fails to deliver measurable progress, governments may be reluctant to treat it as more than a supplemental forum, leaving the UN and established international mechanisms in their current central role.

According to OSW, the evolution of the Board of Peace will also be shaped by how many major powers sign on and whether they are willing to commit long‑term resources rather than symbolic support. The think tank notes that resistance among key UN members, combined with legal and constitutional hurdles in many democracies, could slow or limit the board’s development as a genuine alternative center of multilateral decision‑making.

Taken together, the statements from Trump, the concerns voiced by diplomats and heads of state, and the reservations expressed by UN officials and experts underscore that the Board of Peace has emerged as a politically significant, but highly contested, initiative that is closely tied to Gaza’s reconstruction while raising broader questions about the future of the United Nations and global governance.