The “Board of Peace” masterplan is emerging as one of the most controversial ideas in modern global governance: an ambitious attempt to reshape how powerful states coordinate peacebuilding, reconstruction, and influence in conflict zones, while raising deep questions about legitimacy, equity, and long‑term stability. To understand its implications, we need to look beyond headlines and explore what such a body represents for international law, regional conflicts, and the future of multilateralism.

- What Is the Board of Peace?

- The Masterplan: From Gaza to Global Governance

- How It Compares to Existing Institutions

- Evergreen Principles of Peacebuilding

- Power, Money, and Membership

- Risks of a Parallel Peace Architecture

- The Ethics of Masterplanning Peace

- Aligning a Peace Board With Global Norms

- The Long View: Peace, Power, and Pluralism

- Conclusion

What Is the Board of Peace?

At its core, the Board of Peace is framed as an international organization designed to “promote stability, restore reliable governance, and ensure lasting peace in conflict-affected areas.” Its founding charter describes it as a body that can coordinate reconstruction, economic recovery, and peacebuilding functions in line with international law, with a focus that began around Gaza but quickly broadened into a global mandate.

The organization’s leadership structure is highly centralized, with the sitting US president as chair and wide discretion over appointments, dismissals, and institutional design. Unlike traditional multilateral bodies where power is diffused among member states, the Board concentrates agenda‑setting and decision‑making power in the hands of its founding leadership and a small circle of “global stature” figures appointed for limited terms but dependent on the chair’s confidence.

The Masterplan: From Gaza to Global Governance

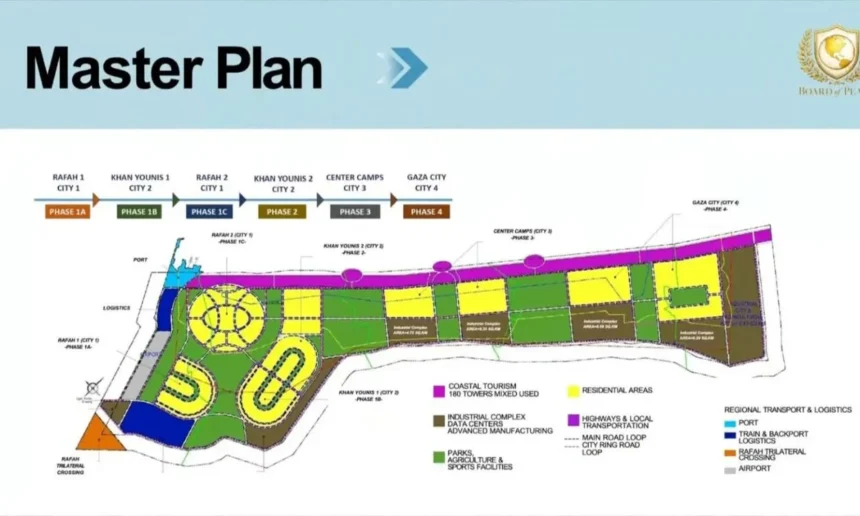

The “masterplan” associated with the Board of Peace began as a reconstruction and development vision for Gaza, featuring large‑scale infrastructure, new economic zones, and phased redevelopment overseen by external actors. Over time, the rhetoric evolved from a narrow focus on post‑war rebuilding into a broader promise: to create a model for transforming fragile or conflict‑affected regions through coordinated security, governance reforms, and private‑sector driven investment.

This masterplan blends three elements that have often been handled separately: security guarantees, economic reconstruction, and political engineering. In practice, this raises enduring questions that go well beyond one territory: Who decides what “stability” looks like? How are local communities meaningfully involved in designing their future? And what happens when strategic interests of powerful states clash with the rights of affected populations?

How It Compares to Existing Institutions

Any attempt to create a new global peace body inevitably invites comparisons with the United Nations, regional organizations, and long‑standing frameworks for conflict resolution. The UN, through its Security Council, General Assembly, and peacebuilding architecture, is built on the principles of sovereign equality and collective decision‑making, even if power politics often distort those ideals.

By contrast, the Board of Peace leans heavily toward a shareholder model of governance, where influence is tied to political clout, financial contributions, and close alignment with the founding nation’s strategic vision. Critics worry that this risks sidelining more inclusive mechanisms and creating a parallel system where a narrower group of states shape outcomes in strategically important regions.

Here, broader debates about reforming global governance come into play. Many independent policy forums and civil society coalitions argue that the world needs stronger peacebuilding institutions, but with more transparency, regional representation, and accountability to affected populations, not less. Against that backdrop, the Board of Peace can be seen either as an innovative workaround to UN paralysis, or as a rival structure that entrenches power imbalances.

Evergreen Principles of Peacebuilding

To evaluate any “board” or framework for peace, it helps to anchor the discussion in widely accepted principles of sustainable peacebuilding. Major multilateral organizations emphasize that durable peace rests on several interlocking pillars: inclusive institutions, human rights, socio‑economic opportunity, and accountable governance.

According to the UN and World Bank, violent conflict is strongly associated with weak institutions, exclusion, and a lack of legitimate avenues for resolving grievances. The UN also highlights that sustainable peace requires local ownership, gender equality, and the meaningful inclusion of youth and marginalized communities in political and economic life. These principles do not change with news cycles; they are grounded in decades of comparative research across post‑conflict societies.

Any credible peace body must therefore do more than mobilize funds or broker elite‑level deals. It must:

- Support impartial justice and the rule of law.

- Protect civic space, independent media, and access to reliable information.

- Prioritize trauma‑informed recovery and social healing.

- Foster inclusive economic growth that reduces inequality and avoids fueling new grievances.

If the Board of Peace is to live up to its name in an enduring sense, it will need to align its practices with these long‑standing norms rather than treating peace as a narrow security or infrastructure project.

Power, Money, and Membership

Beyond its formal mission, the Board of Peace raises lasting questions about who gets to define peace and under what conditions states can join or influence its direction. Reports suggest that membership involves substantial financial commitments, signaling that participation is tied to both political alignment and the capacity to contribute large sums of money.

This blends peacebuilding with a club‑style governance model that favors wealthier states and those willing to accept the founding leadership’s political terms. While financial responsibility is essential for any major initiative, a peace framework that implicitly prices out poorer nations risks replicating the very inequalities that global development institutions warn can fuel instability.

Global bodies such as the World Bank and IMF have long stressed that broad‑based development and reduced inequality are central to preventing conflict. If a peace board’s architecture reinforces economic and political hierarchies instead of democratizing voice and participation, it may be more a tool of influence projection than an engine of shared security.

Risks of a Parallel Peace Architecture

One of the most enduring debates around the Board of Peace concerns whether it complements or competes with existing multilateral structures. Supporters argue that in a world where the UN Security Council is often deadlocked, alternative frameworks can act more decisively, especially in urgent crises. They see the Board as a way to mobilize resources quickly, bypass institutional gridlock, and tie peacebuilding to concrete economic incentives.

Skeptics counter that creating powerful parallel bodies can erode the legitimacy of universal institutions, fragment international law, and make it harder to coordinate responses across overlapping mandates. When competing centers of authority emerge, states can “forum shop” for the venue most aligned with their interests, potentially undermining coherent standards on human rights, accountability, and the lawful use of force.

For ordinary people in conflict‑affected regions, the danger is that geopolitics overshadows their basic rights and needs. If peace becomes a bargaining chip between powerful blocs playing in multiple arenas, communities on the ground may experience long negotiations and ambitious masterplans—without seeing meaningful improvements in security, dignity, or self‑determination.

The Ethics of Masterplanning Peace

The idea of a “masterplan” for peace is alluring because it suggests control, clarity, and direction in situations that are otherwise chaotic. Detailed blueprints for reconstruction, governance, and investment can appear visionary, especially when accompanied by striking visuals of rebuilt cities, new corridors, and reimagined economies.

Yet peace studies and transitional justice scholarship emphasize that genuine reconciliation and institutional transformation cannot be scripted from above. Trust is rebuilt through participatory processes, recognition of harm, and long‑term commitment to justice, not simply through large physical projects or foreign‑designed administrative templates.

A lasting peace architecture therefore needs to balance strategic planning with humility: acknowledging that affected communities are not passive recipients of a masterplan but co‑authors of their own future. When any board or consortium treats local populations primarily as objects of design rather than as rights‑bearing partners, it risks breeding resistance and perpetuating cycles of domination and backlash.

Aligning a Peace Board With Global Norms

For a body like the Board of Peace to evolve into a constructive force rather than a polarizing one, several evergreen criteria can guide its development:

- Clear, limited mandate

Defining scope carefully—whether focused on post‑conflict reconstruction, security guarantees, or economic coordination—can reduce fears that it seeks to supplant universal institutions or rewrite core norms. - Embedded human rights standards

Aligning decisions with existing human rights conventions, humanitarian law, and established accountability mechanisms helps prevent ad‑hoc arrangements from undermining hard‑won global standards. - Inclusive membership and voice

Designing representation that reflects regional diversity, development levels, and civil society perspectives can counter the perception of a narrow geopolitical club. - Transparency in finance and decision‑making

Clear rules on financial contributions, procurement, project selection, and conflict‑of‑interest safeguards are essential to maintain trust and avoid the sense that peace is being commodified. - Local ownership and participation

Incorporating community leaders, women’s organizations, youth networks, and local authorities into planning and oversight structures aligns with the widely recognized principle that local ownership is central to sustainable peace.

Without such safeguards, any peace board—no matter how ambitious its masterplan—will face enduring doubts about whose peace it serves and whose power it entrenches.

The Long View: Peace, Power, and Pluralism

The story of the Board of Peace fits into a much larger, timeless narrative: how major powers adapt global governance to their interests while claiming to serve universal ideals. Throughout modern history, new institutions have emerged in moments of crisis or transition, from post‑war alliances to financial compacts and regional unions, each reflecting a particular balance of power and vision of order.

What makes this moment distinctive is the intensity of debate around legitimacy. With rising geopolitical competition, mistrust of elites, and the visibility of conflict through digital media, any new global framework faces scrutiny not just from governments, but from global civil society, independent experts, and engaged citizens. In such an environment, claims to be a neutral “board of peace” must withstand interrogation from many directions.

Over time, the true legacy of this masterplan will be measured less by its launch rhetoric and more by its track record: whether it reduces violence, strengthens just institutions, respects local agency, and complements rather than corrodes the broader ecosystem of international cooperation. Those are the criteria by which any enduring peace project will be judged, regardless of who chairs it or where it is announced.

Conclusion

The Board of Peace represents both an opportunity and a warning: an opportunity to rethink how resources and political will are mobilized for post‑conflict recovery, and a warning about the risks of concentrating authority in ways that may sideline more inclusive institutions. The masterplan surrounding it will only foster genuine stability if it internalizes long‑standing principles of justice, participation, and shared governance that global institutions and research have highlighted for decades.

Ultimately, any claim to steward peace must pass a simple but demanding test: does it leave societies more capable of resolving their own disputes peacefully, protecting rights, and offering fair opportunities to all? If the Board of Peace can move in that direction, it may become part of a more plural, resilient peace architecture; if not, it risks joining a long list of ambitious frameworks that promised transformation but delivered little more than a new arena for power politics.

After looking at the “Culture of Violence Index 2025” of peace researcher Franz Jedlicka, I think something must also change within Palestine families. According to UNICEF there is already much violence against children! Also the books of Nancy Hartevelt-Kobrin are helpful to understand cultural obstacles to peace in the MENA region.